|

Three of Paul Jennings’s children—all born as slaves belonging to their mother’s master (a neighbor of James Madison)—outlived him: daughter Frances and sons John and Franklin. Author Beth Taylor interviewed living direct descendants in each of these three lineages to learn their family histories. The book, A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons, contains over 20 illustrations—maps, photographs, and a full family tree. Posted on this website are additional photographs that could not be included in the book. Paul Jennings’s daughter Frances and her descendantsPaul Jennings’s daughter Frances Jennings was born a slave in Orange County, Virginia. She was freed by the terms of her master’s will in 1856, and died about 1888 in the Washington DC poor house. Frances had two sons, Taylor and Hayward. Taylor moved to Ohio as a young man but Hayward established himself in northwest Washington with a position as a butler. Here is a likeness of Hayward:

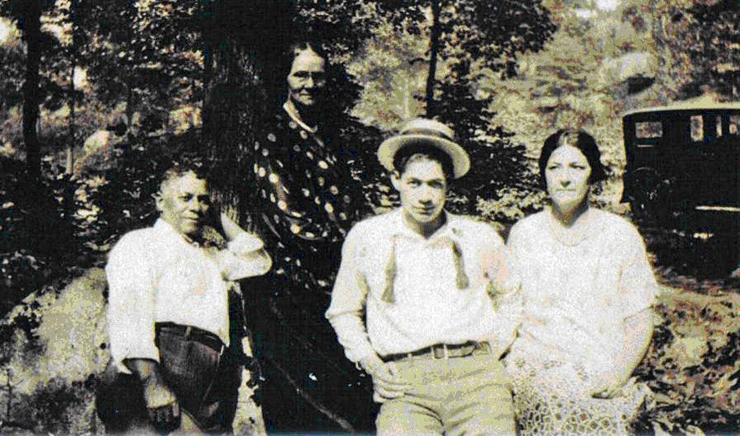

Hayward married Cordelia Johnson and they had five children. The eldest was Frances, named for her grandmother. Frances and her husband, Thomas Hughes, had three children. One of them, Albert Lloyd Hughes, is pictured here with his parents and grandmother:

Another of their three children was the mother of Elsie Styles-Harrison. Elsie Styles-Harrison and her two grown daughters live in Pennsylvania today.

Elsie and daughter Lisa Harrison Collins were among the Paul Jennings’s descendants who gathered for this extended family photograph on the steps of the Montpelier mansion. When the Jennings descendants gathered at the Montpelier estate, their ancestor’s Virginia plantation home, in February 2009 (six months before their tour of the White House), their coming together was the first extended family gathering in nearly fifty years.

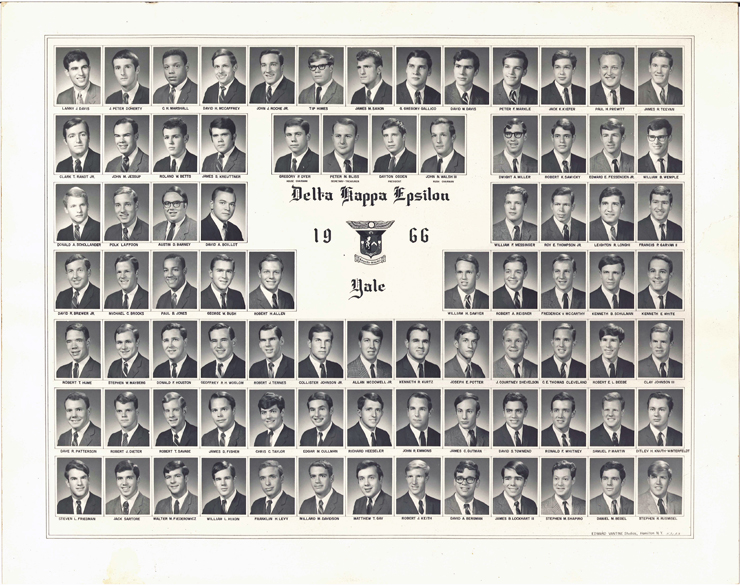

Paul Jennings’s son John and his descendants John (or Jack) Jennings was, like his sister Frances, freed in 1856. For a good many years, even after he married Louise Jackson, he lived with his father at 1804 L Street in northwest Washington. Among his five children was a daughter Pauline, presumably named after his father. Pauline married Charles Marshall. Though the son of a slave, Marshall became an M.D. and he and Pauline acquired a house in Georgetown. Their great grandson, Raleigh Marshall (a graduate of James Madison University), still lives in that house. On the day in August 2009 that the Jennings descendants had their private tour of the White House, Raleigh was interviewed at his home by Washington Post feature writer David Montgomery. To read the story, click here. ♦ It would seem that connections with Presidents is an ongoing theme in the Jennings family. Below is a photograph of Delta Kappa Epsilon members at Yale from 1966. Paul Jennings’s great great grandson (Raleigh’s father), Charles H. Marshall III, is pictured top row, third from left. Can you find a future U.S. President in the group? Hint: to be a member of DKE, one must be equal parts “gentleman, scholar, and jolly good fellow” (and get through the hazing).

Paul Jennings’s son Franklin and his descendants Franklin Jennings was emancipated from slavery in January of 1856 at age 20. He lived a long life, dying at 90. His granddaughter Sylvia became the family historian, having spent many of her growing up years in the home of her grandparents (Franklin’s wife Mary was from the same historic neighborhood in northwest Washington and she lived to be 99). Sylvia Jennings Alexander died in October 2009. Beth Taylor, the author of A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons, had the great good fortune to get to know Mrs. Alexander over the last year and a half of her life. There are several photographs of Franklin Jennings in the book. Here is one of Franklin’s son Hugh, Sylvia’s father:

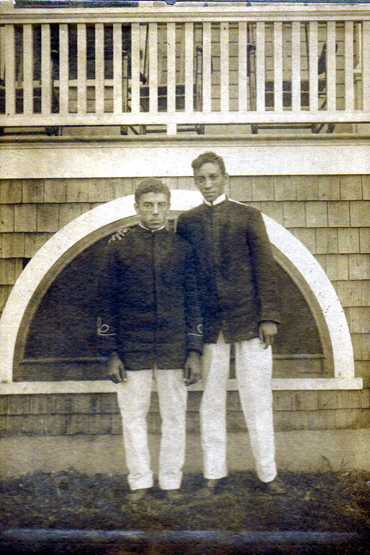

♦ Like Sylvia, Henry Early was also a grandchild of Franklin Jennings. Here is a photograph of Henry Early. He is the one on the left; he and his buddy were working at a resort when the photo was taken.

Paul Jennings’s devotion to the Madisons:

Posted: 01/3/2012 04:54 PM EST My great-great-great-great grandfather, Paul Jennings, expressed a great virtue every time he reached into his pocket, or brought household staples to help care for Dolley Madison. After all, Dolley had sold him for $200, despite the wishes of her deceased husband, the president of the United States. In modern times we often call the empathetic bond between victim and captor the Stockholm syndrome. How much of this psychological tendency actually influenced Paul? I think that this condition emerged organically—a dynamic of the culture of close servitude. It was undergirded by, and borne through the Madisons’ kindness toward their slaves. I highly doubt that this was something particular to Paul. However, only when this dynamic is coupled with an intelligent and benevolent character like Paul’s, can a greater capacity to love be formed. Transgressions and character flaws can be overlooked and forgiven, when love steps up to the plate. We may never really know what motivated my great grandfather, but I do believe that this is another example of Paul expressing love in its finest form, altruism. ♦ Living with the Legacy:

Posted: 01/2/2012 10:31 PM EST I have the honor of being both a Jennings descendant and a Marshall descendant. When these two families came together, the result was a family that truly felt purpose-built to honor and protect freedom. My definition of freedom is the ability for you to pursue your dreams and aspirations without sabotage from another. It is my firm belief that this was the consolidated goal of the many civil rights leaders that have preceded us. Freedom as I have defined is an impossible goal, there are always going to be those who will actively try to control you (either directly or indirectly) for their benefit. Due to this, if we become complacent in the defense of our freedom, we will soon find it will escape us. The attackers of freedom have a wide arsenal of resources, influence, and propaganda at their disposal, and it is our responsibility as the upcoming generation to maintain vigilance, and protect the freedoms for which many have suffered to afford us. What the family legacy has passed onto me is the responsibility of doing what I can to rally others around this cause, and to encourage the pursuit of this goal.

Henry Early’s grandson David Early, Sr. is today an editor at the San Jose Mercury News. His article on the what the election of Barack Obama, our first African-American president, meant to him as the descendant of Paul Jennings was posted on 13 January, 2009. A reflection: To be black in America on Obama's Inauguration Day

Posted: 01/13/2009 05:32 PM PST Today, I will not be at work. I will gather my family and friends and together we will watch the swearing in of Barack Obama as President of the United States with all the pride of parents at a baptism. To be black in America on Jan. 20, 2009, is to know a deep satisfaction scarcely imagined by generations past. A blizzard of giddy emotions will envelop the souls of millions of black folks in America and all over the world. But because Obama was embraced and elected by a wide ethnic diversity of voters, the sense of celebration is sweeter and even more profound. Well into my sixth decade, this is an event I never expected to see. On election night, working in the midst of a bustling city room, I settled in and expected a lengthy run of embattled counts and political fisticuffs. But scant hours later, when the election of the 44th president was a first-ever, done deal, I was completely unprepared. All over the newsroom people from a range of backgrounds applauded the nation that had freed itself from 232 years in social, racial, intellectual and political shackles. There were high-fives, hugs and hallelujahs. Even McCain-supporting Republicans seemed to ruefully acknowledged the monumental step America had taken. I was standing behind a chest-high wall when the televised bulletins obliterated my knees. When someone saw me swiftly drop behind that wall, they shouted, “Omigawd he fainted!” Not a chance. Nothing could have taken me away from one second of that evening of surreal delight. I had fallen into a nearby office chair, but suddenly tears burned my closed eyelids. In an instant my mind was surveying past a bleak landscape of cruel, sepia-toned images — slaves in chains, jumping brooms, being sold, getting whipped, having babies and enduring lives of horror without end. But what I felt, shockingly, wasn't rage. It was an unexpected healing of the heart. On that continuing silent mental road trip, I revisited the agonies of civil rights marchers going hopelessly against brutal decades of Jim Crow segregation that crushed so many lives in court, athletics, housing, education and employment — opportunities forever lost in blood. Civil rights is not mere history to me. My childhood was haunted by Emmett Till and lit by Rosa Parks. Her framed photograph is the first you see as you enter my home. When four little black girls were blown apart in a Baptist church, when two white and one black civil rights workers were murdered, when Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, I was an aware teenager who feared for my kinfolk living in harm's way all over the Deep South. But on Election Night '08, I felt warmth and calm as I contemplated my late parents, uncles, grandparents and so many family and friends now gone. I knew they'd just giggle over this mighty American miracle. I even phoned a few elders, just so I could hear various, bright-red versions of the phrase: “Never in my lifetime did I ever expect to see this!” And finally I thought about my special ancestor, Paul Jennings, born in 1799 as a slave on James and Dolley Madison's Montpelier plantation. My great, great, great granddaddy Paul would go on to live in the White House and write “A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison,” now considered an insightful, historical document. Ultimately, he'd buy his freedom for $120 from Sen. Daniel Webster and become a government employee, socialite and homeowner in Washington, D.C., my hometown, where he died in 1874. But election night, I found myself imagining a 10-year-old Paul telling an amused Master James, who was about to become the fourth U.S. president, how one day, a black man would be elected to that same post. As the principal author of the U.S. Constitution and the Federalist Papers — documents long on ideals but, for some, shaky on execution — I conjured an ethereal Madison benevolently watching over Obama being sworn in, exactly 200 years after he was. Somewhere up there, I hoped all the founding fathers and mothers, and all those fallen slaves, civil rights workers, activists, victims and protesters were smiling down on the prize of their heroic labors. Obama's election, to some degree, means all the work and tragedies finally paid off. And much credit is due to plenty of human good that also transpired — peaceful sit-ins and boycotts; those who backed the Voting Rights Acts and those who argued and ruled in Brown vs. Board of Education. And a diversity of untold individuals and organizations created affirmative action — the most potent and misunderstood force of them all for breaking down the nation’s walls of unfairness. Along with many around the world, I have enjoyed an African-American being the source of inspiration for many: Men and women. Young and old. Rich and poor. Healthy and handicapped. Professional and vocational. Gay and straight. Urban, suburban and rural. Educated and self-taught. American, immigrant and foreign. Black, white, Latino and Asian. Forty-five years ago Martin Luther King Jr. shouted “I have a dream today.” But at this intense moment, those are brand new words for my healing heart. And in thinking about my children — David Jr. and Dionne — and my three grandchildren — David III, 11, Dimitri, 7, and Victoria, 10 months — this election makes genuine all those puffy sentiments about hope and dreams and aspirations. So before Obama comes under attack from the many remaining forces of ignorance and bigotry, I will revel with my family. Rambunctious Dimitri, during the telecast, will doubtlessly ask to go out and play. “No baby boy, not right now,” my son will say, giving me a knowing smile. “You need to sit with us and pay attention to what’s going on here. One day, you’ll be glad you did.” His grandfather surely will for the rest of his life. ♦ Dedication of former slave dwellings at Montpelier

Like David Early, Margaret Jordan is descended from Paul Jennings via her grandfather Henry Early. On 25 September 2011 the South Yard where Jennings lived at Montpelier, Madison’s Virginia Plantation, and where the former slave dwellings and other outbuildings are now being reconstructed, was dedicated. A special guest on the occasion, Margaret Jordan offered the following remarks: Good afternoon. It is an honor to be asked to speak to you this afternoon and to share with you why I believe the South Yard here at Montpelier is an important site. First let me introduce my family members who are here with me today. My daughter Fawn Jordan and my cousin Mary Alexander. In February 2009 at a Jennings Family Reunion here at Montpelier, I first visited this site, which was just beginning to be explored. Thanks to Elizabeth Taylor, who organized the reunion and was then the Director of Education here at Montpelier, I learned more about my great, great, great grandfather Paul Jennings. For the first time, I met cousins that I never knew. I was introduced to Montpelier and the Madison’s in a new way. And, I had one of the most moving experiences in seeing on a neighboring plantation, the home of Fanny Gordon, Paul Jennings’s wife and my great, great, great grandmother. That visit to Montpelier had an indelible impact on my family and me. My great, great, great grandfather Paul Jennings was born in 1799 here at Montpelier. While there is little known about his mother, my fourth great grandmother, both Paul and his mother are thought to have lived here in the South Yard. At 10 years of age, Paul was one of several Madison slaves to travel with them to the White House. When the Madisons returned to Montpelier for their retirement, Paul once again was thought to have lived in the South Yard slave housing. So for my family the South Yard is a vital piece of our family history. We are unusually fortunate to know so much about Paul Jennings. And seeing the places where Paul, his mother, his wife and children lived has brought to me unbelievable emotional and intellectual context to my sense of family and who I am. Being present at this site helps me to envision the life, the daily activities, the environment, and the place where Grandfather Paul was born, grew, played, and worked. This place contributed to his self-identity and his character. While there may be little information about other Montpelier slaves, particularly those others who lived here in the South Yard, this restoration becomes critical to a deeper understanding about them. I believe that every slave who lived and worked here had an important story to tell. If they and Grandfather Paul Jennings were speaking to us today, they would urge us to pursue learning about them and their stories. So many people today are thirsting for more information on their ancestors, their genealogy, and their family’s place in America’s history. Whenever I share the story of Paul Jennings, it almost always sparks in the listeners a desire to share their families’ history. And, frequently this discussion creates a sense of urgency in them to further explore their genealogy. Recently, one person spent twelve hours after a dinner meeting researching and finding several of his ancestors. A historical site such as the South Yard will undoubtedly fuel the thirst of many to learn more about their families and therefore about themselves. It should spark in visitors an interest in learning more about enslaved African American people here at Montpelier and elsewhere. It can bring to life the history one has read. More importantly, visiting this site and learning more about the slave life here will hopefully lead to a greater understanding of the limitations on the freedom and individuality of slaves. And, hopefully it will lead to a greater understanding and appreciation of not only their sacrifices but also their strengths and their contributions to our nation. The restoration of this site will help us to see, to understand, to better imagine what the day-to-day life might have been for the slaves who worked and lived here. Stop for a minute, close your eyes and hear the chatter of people as they go about their work. Hear the snores of a weary person after a very long day. Hear the laughter, and hear the crying. Hear the worry, and also the singing. Was that the crunch of snow as someone leaves the main house for his cabin? Do you hear the wife fussing with her husband? Then there is the child being praised. And oh are those the sweet words between lovers. Yes, this place can help us imagine the lives of the people who lived here. This site will contribute to a growing body of knowledge about these individuals and their community. What did these hard working people contribute to their community, to the Madison’s and to this country? As the archeologists piece together the items found at this site and extrapolate and interpret who were the slaves, what they wore, how they lived, the items they used for everyday living and the nature of their work, it will give us a greater sense that these were important individuals, women, men and children. I want to thank Christian, Director of Education and Amy Cotz, Research Associate for the African-American Research Initiative here at Montpelier for organizing this day and inviting us here. And thank you to the Archaeology staff for their diligent and incredible work on this excavation. Let me acknowledge and thank Beth Taylor for her painstaking research on Paul Jennings which began here at Montpelier and has culminated in her book, A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons. The book will be released in January. Thank you to Montpelier’s Foundation’s leadership, in particular Michael Quinn for their sensitivity to and appreciation of the enslaved people of Montpelier. And in closing let me quote George Morgan, a genealogist whose words speak for how I feel: “Family is forever! That is a lesson learned from parents, aunts, uncles and grandparents as they exposed me to their pride in their family history. Their stories and enthusiasm sparked an interest in me to explore and learn more on my own. History and geography are no longer just names, dates and places. They become the world stage on which my ancestors and family members actively participated, observed, and/or were affected. That perspective has served me well over times because it encourages me to always try to place my family into context with the places, periods and events of their lives and to view them as real people.”

♦

Could you be a Jennings descendant? For her research on A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons, Beth Taylor also followed the line of Paul Jennings’s son William. After his service in the Civil War, William settled in Carlisle, PA. He and his wife had several children before William died c1872. Identification of descendants from this line about the year 1912 included Anna Jennings of Ardmore, PA; Mrs. Lewis Densy of Pittsburgh and Mrs. George Athens of Carlisle (one of these married women would be Avena Jennings and the other Sarah Matilda Jennings); and Fannie Jennings (with her children Gilbert Jennings and Magnolia Jennings) of Carlisle. Also of interest were two grandchildren of Frances Jennings, sons of Hayward, who were particularly light-skinned and moved to New York City between 1917 and 1920 and “passed” for white. Both young men, Hayward T. (b. 1882) and Ralph (b.1888), kept their names but married white women and can be followed through census and military records, in the case of Ralph up to 1942 when he was living in Queens. This photograph of a seaman is believed to be of one of the two brothers:

|