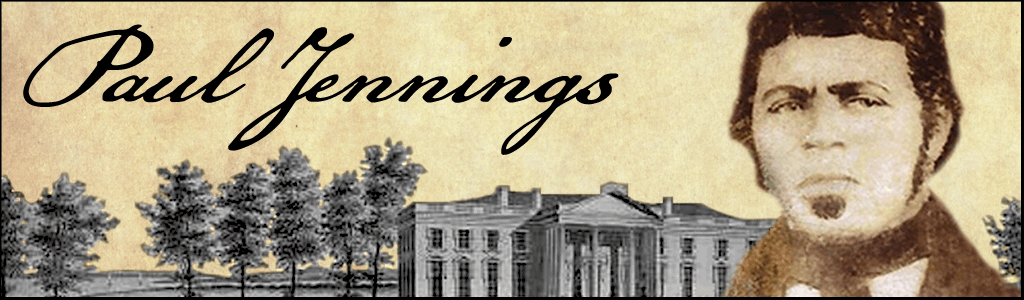

Paul Jennings was born a slave at Montpelier, James Madison’s Virginia Plantation in 1799 and died three-quarters of a century later, bequeathing a house and prized property in northwest Washington D.C. to his sons John and Franklin. In 1820 Paul Jennings, in the prime of life, was promoted to the position of James Madison’s personal manservant at Montpelier. At this point, he had already served James and Dolley at the White House and participated in the stirring events in Washington surrounding txhe War of 1812 that he would later chronicle, including the burning of the White House and the rescue of the portrait of George Washington. After two presidential terms the Madison household withdrew in 1817 to their Virginia Piedmont plantation. As manservant, Jennings was responsible for Mr. Madison’s wardrobe and toilette, and accompanied him on his travels to Charlottesville and Richmond. As the years went by and Madison’s health failed, he leaned on Jennings’s arm for support. Jennings was present when the end came for the ex-president and he left the only eyewitness account.

The widow Dolley returned to Washington in 1837 with a few household servants including Jennings. This meant separation from his wife Fanny and their children in Virginia. There had been five all told—Felix, William, Frances, John and Franklin. During a visit in the spring of 1844, he found his wife ailing; “Pore fanney,” he wrote to Sukey back at the city house, “I am looking every day to see the last of her.” Fanny Gordon Jennings died on August 4th of 1844, the same year that Dolley sold Montpelier. Back in Washington, Jennings had reason to expect his freedom from Dolley one day. She had written as much in her will of 1841: “I give to my mulatto man Paul his freedom,” the only slave so treated. But Dolley faced tough times. She hired Jennings to President James Polk at the White House in 1845 and, according to an abolitionist newspaper that had picked up Jennings’s story, kept the money “to the last red cent.” Indeed, despite the terms of the will, it was reported that Jennings, fearing Dolley’s “wants might urge her to sell him to the traders, insisted she should fix the price, which he would contrive to pay, whatever he might be.” Jennings instincts were correct. Dolley sold him in September 1846 to Pollard Webb, an insurance agent in the city. The price was low at $200. Only six months later, Jennings was purchased by Senator Daniel Webster who wrote up the following arrangement, “I have paid $120 for the freedom of Paul Jennings; he agrees to work out the same at $8/month, to be furnished with board, clothes, washing…his freedom papers I gave to him.” Jennings was now a free man. He would remain an important member of the black community of northwest Washington for the rest of his days. In 1848, he acted with other abolitionists to plot a major, ultimately unsuccessful, escape attempt to the north of 77 slaves (including a run-away slave of Dolley’s named Ellen Stewart) on a schooner named Pearl. In 1849, Jennings remarried. His new wife was a mulatto woman from Alexandria, Desdemona Brooks, free because the daughter of a white woman. Jennings continued to work for Daniel Webster, who in 1851 issued his former dining room servant a recommendation (“honest, faithful and sober”) which Jennings presented to acquire a job at the pension office in the Department of the Interior. Jennings worked as a government employee—albeit laborer—for about 15 years. There in 1862 he met a new co-worker from Massachusetts, John Brooks Russell. Russell, an antiquarian and contributor to “The Historical Magazine and Notes and Queries Concerning the Antiquities, History and Biography of America,” found Jennings’s story of his association with President Madison fascinating. In January 1863, “A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison” appeared in the magazine. Russell identified himself only as JBR and submitted the history Jennings shared with him “in almost his own words.” Two years later the Reminiscences were published in book form. In the 1850s Jennings reconnected with his surviving children in Washington. He purchased two small, wood-frame houses on L Street near 18th Street NW for $1,000 each. He lived at 1804 L Street with his wife and younger children, while daughter Frances and her two sons lived next door. Sons John, Franklin, and William all joined the Union forces in the Civil War. In his 1870 will, the twice-widowed Jennings and grandfather of six, referred to a new wife-to-be. In fact he married Amelia Dorsey on September 14 that same year. Paul Jennings died at home in May of 1874, a gentle close to a long and eventful life with many chapters. |